In November 2024 the House of Commons approved the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill following an extended debate within and without of the houses of Parliament. This centred not so much on the central questions around utility provoked by the singular act itself, but on the context, the creation of a space within which it can happen safely, and importantly with sufficient autonomy. Serendipitously emerging into this terrain, the ICA’s exhibition of Jean Luc Godard’s final films Scénario(s), Exposé du film annonce du film “Scénario(s), and his creative notebooksvalues Godard as an artist at the end of his life: in 2022 Godard elected for a voluntary death. As reported in the French paper Libération, this was not because he was sick but because ‘he was simply exhausted’. Importantly he also wanted the decision ‘be known’, implying that his death and his art existed on the same register of purpose. As a thinker who was largely concerned with how to live within, in spite of, and exceed the striated social and psychic cartographies of late capitalism, his final films are his generous bequests on autonomy in life, art and death: what it means to live, create and die by one’s own hand.

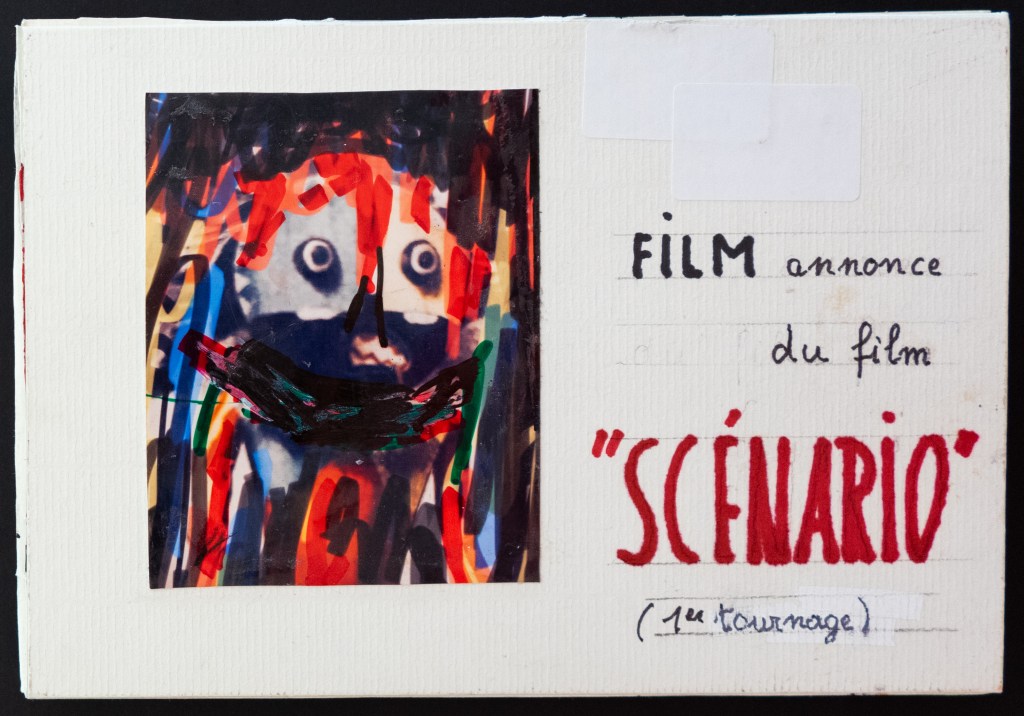

Scénario(s) was completed on the last day of his life. It is accompanied by another longer film Exposé du film annonce du film “Scénario(s) which documents the construction of the Scénario(s). Exposé… is a walk-through of Godard’s storyboard book which, exhibited along with notes and facsimiles of five other notebooks bursting with reference and citation. Taken together with the two films these disclose hiscreative methodology annunciating how Godard, in life, art and death, ‘thought’ with his hands.

Constructed as a collage the book foretells both the form and content of Scénario(s). Taken together the films process their own operating system, recursively observing both the what happens in the film, and simultaneously how it happens. The book is determined by concrete ideas – the ‘five fingers’ as he names them in the voice over – that invite expansion and improvisation: an unfolding of socialism against capitalism; women against socialism; children against women; animals against children; and nature against animals. In the final scene of Scénario(s), perhaps exhausted by the rigours of language, naming and claiming, Godard cites Sartre: ‘taking fingers to illustrate the fact that fingers are not fingers is less effective than taking non-fingers to illustrate the fact that fingers are not fingers’. Commensurately, the dialectal arcs of the ‘five fingers’, familiar as sites of resistance in Godard’s oeuvre, precipitate an a-temporal cascade of images and references. The co-ordinates of Hamlet, Stravinsky, Badiou, ‘fake news’, Pasolini, Melancholia1 by Durer, the films of Russ Meyer, nature and so on create the impression of an accumulation of debris out of which something eurythmic might suddenly appear. At odds with the seemingly literary character of his work – his films seem to demand to be as much read as viewed – Godard notes in the accompanying books that ‘it’s in the desert that you have to go looking for the image…you don’t shed light on things with the alphabet’. That this threatens to precipitate a ‘mysterious conclusion’ and ‘one last image that doesn’t mean anything’, with all its messianic overtones is a reassurance to those of us who can sometimes struggle to accompany Godard as he exceeds the conventions of storytelling.

As Godard walks us through the content of the notebook in Exposé we encounter the man himself, lucid despite being ‘simply exhausted’. As we meet him again in a very affecting moment in the final shot of Scénario(s), reading out loud Sartre’s Fingers and Non-Fingers he cites ( the German painter) Wols, who cites (the Chinese philosopher) Chuang Tzu on the determinations of naming, how ‘a path is formed by constant treading on the ground. A thing is called by its name through the constant application of the name to it’. This is his gift in his last moments, indeed tired and exposé, reflecting on one of the central theoretical concerns threaded through his work that was cued up in Breathless (1960), entertained in Alphaville (1965), contended in The Image Book (2018): the disposition and adequacy of language.

The filmic action of Exposé centres on Godard’s hands and how he edits the collage-book through cuts and pastes, how the pace and momentum is generated through push, tear, and gesture, such that the process seems as much somatic as thought. If Godard’s films combine reading and seeing, Exposé and Scénario(s) work as a co-joined exposition of how these demands are created through a reticulated utterance of choreographic purpose: like a dance the meaning of the work unfolds by allowing a lifetime’s accumulation of text and image to pass through the ‘khora’ of Godard’s body, which works like a sieve, to be ‘thought’ by his hands.

This form is gestated from his early work – indeed reticulation is shot through his entire oeuvre – realised in Histoire(s) du Cinema (1988), reflected on in Goodbye to Language (2014), to reach a final but inconclusive exposition here. His contemporary, the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze (who significantly also elected to a voluntary death) references Godard extensively in his books Cinema 1, Cinema 2, and Negotiations. He describes how he replaces representation with kind of collage-modulations to construct a near-abstract cinematic form that privileges affective body experience over visual signification (much like the painter Wols).

These open up to, in Deleuzian terms, contagions that allow becomings: the babbling form of Scénario(s) is processual rather than progressive. For Deleuze, in Godard’s cinema ‘what disappears is all metaphor or figure… instead of one image after the other there is one image plus another’ creating a cinematic plane with a consistency that is resistant to the identification of fixed points of meaning. The viewer of Scénario(s) is neither in the position of the camera, experiencing a constructed subjectivity, nor in objective receipt of documentary. Exceeding a structured call and response between film and viewer, for Deleuze Godard ‘initiated a cinema of the body’: a lack of a conventional boundary between subject and object, viewer and viewed, objective reality and subjective perception leads to a jumbling of viewpoints. Godard choreographs all parties with ‘images and sequences (that) are no longer linked by rational cuts which end the first or begin in the second, but are relinked on top of irrational cuts, which no longer belong to either of the two and are valid for themselves’.

Scénario(s) is split into two co-responding parts. Godard releases the viewer from the armature of the centring metaphorical reference – subjects and images, such as the sound of an MRI scanner, the figure of a man in a desert – are repeated and reproduced, reinforced and diluted in each, creating a porosity between them. And in turn this reflects the method of Exposé. Scénario(s) DNA Fundamental Elements implies a mapping, the material cartography of Godard’s body/world,then part two MRI Odyssey implies revelation, the metaphysical uncovering of an embodied journey to the end of life. If Exposé shows how Godard is embodied in Scénario(s), in turn in Scénario(s) the content hums and clatters, it impacts directly on the nervous system through affect and pulls the viewer into assemblage with the film itself. In The Image Book Godard cites French theorist Denis de Rougement, who, relying on Heidegger, argued that ‘the true condition of man’ is to ‘think with his hands’. The human is set apart as a demonstrative, signifying animal, but ‘handiwork’ also sets them apart from themselves: for Heidegger, hands ’think’, and like Godard they protest against the hand’s own effacement or debasement in the industrial automation of modernisation.

Appearing on perfectly disparate registers, Godard’s earlier works and his final act can be treated as theoretically coetaneous events, each catalysing the other. His commitment to a kind of somatic radical activism, a lifelong showing, demonstration, in Jacques Derrida’s thought a ‘monstration’ of a cinematic form that worked against the ideological institutions of late capitalism through an artisanal cinema of thought as Hand-Werk. And with the commitment that is unique to the signifying animal, the ‘monstrous’act of a voluntary death by one’s own hand. That Godard wanted his exit to be known speaks to the thought that was threaded through this plex philosophers’ work, and the actions in his life: with hands he had divined a path for thinking in the abyss of being, so that finally ‘the hand ‘has’ man, occupies…man …in his essence, the hand’s gesture for making the word manifest’: Scénario(s) is left behind to be read and seen as companion to his voluntary death, Godard’s final act of ‘manuscripture’.

Charlie Hardie

Leave a comment