It’s over decade ago now since philosopher and feminist theorist Rosi Braidotti recited ‘almost’ a love poem to the European Union in 2013, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTNFD1v7zxU&t=344s) reminding the audience in session why the Union was created – to realise what once seemed the reasonable project of a borderless de-striated region of the world that would allow for the smoothing out of collisions – social, political, economic – both within its territories, and equally, the encounters with those populations and entities without. Braidotti’s concern was that this simple dream had become a utopia, a lost future now subject to nostalgia. But she also reminds the audience of the context of the Unions’ conception in the aftermath of the Second World War, at heart moved by one single motive: to create a cosmopolitan communion which would prevent the type of wars that ravaged Europe in the Twentieth Century. The events of the last decade now make Braidotti’s anxieties seem quaint. Brexit weakened the bonds of Europe in all respects – not least the dissolution of the idea of any kind of European army. Now that Trump is refiguring NATO as a corporation to acquire inventory, European politicians are feeling somewhat exposed: they simply do not own enough shares in the enterprise, nor do they have any other investments. It feels like Europe could be entering a terminal phase as a fatally damaged cosmopolitan communion is now eclipsed by a neo-colonial agenda.

The migrant crisis of the last decade or so is the neccessary corollary to this unfolding. Key to the slow dismantling of unity were the chaotic ethical ‘collisions’ around the Mediterranean. These tested the Unions ideological efficacy in a basic respect and has revealed the cultural inheritance of the European Enlightenment to be unassailable. Over the last decade or so Europe has been required to accomodate populations displaced by events with which the West has been complicit: the entreaty to be hospitable to strangers has provoked the European Right’s refusal to relinquish the integrity of regional territories, let alone National or intra-National ones, exposing how European ideas of social and political community still precariously rely on Immanuel Kant’s ‘Project for Perpetual Peace’ (which has served as a model for the League of Nations created after the First World War, and the United Nations after the second) now contemporary scholarship accepts Kant to have been ironic, as one of ‘the philosophers who dream that sweet dream of peace’.

Hospitality

In the aftermaths of the wars of the twentieth century politicians, philosophers, artists and designers imagined peace and the possibilities for a new kind of European hospitality. Some figured this as a structural challenge and produced speculative spatial regimes. A utopian and poetic solution of the 50’s, inspired by the plight of categories of the European nomad, the Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys created the architectural solution for a cosmopolitan world-citizen-as-nomad: a ‘‘New Babylon’ where under one roof, with the aid of moveable elements, a shared residence is built; a temporary constantly remodelled living area; a camp for nomads on a planetary scale’. Constant acknowledged that the ‘cosmopolitan hospitality’ such as that proposed by Kant could only exist if it is a right that exists between equals through a symmetry of property or civic status, and how his is impossible as an inalienable right for the particular nomad or migrant. A host has to be able to empathise – to be able to easily imagine himself in the place of his guest, in order to ‘alienate’ the mastery of his territory to the guest. This is dependent on an equivalence that is undermined by cultural asymmetry and even more broadly, economic inequality. Figured in the light of a post war Europe as palimpsest where re-configured borders and the mass movement of peoples and the emergence of a mongrel European as an opening to re-inscribe over an erased past, Constant’s fully speculative vision was of a future for ‘Homo Ludic’, a man freed from the constraints of territorial striations, civic life and work through the primacy of technology, free to range over the ‘common property of the surface of the earth’.

Projects like this congeal with Kant, who declares at the outset of ‘Perpetual Peace’ that what he proposes was an impossible project for the living; both for the philosopher-as-dreamer and for ‘the sagacious statesman who knows the world’. As a thinker situated in between a philosophical utopia and the real world he apologises for complacency: ‘a mere pendant who may always be permitted to knock down his eleven skittles at once without worldly wise statesman needing to disturb himself’. If not entirely ironic or satirical of the philosopher, then Kant hints that this treatise addresses an impossible problem, or one that at best can only hopes to ‘gradually work out its own solution’1. For Kant the need for a legislative peace is produced by the common possession of the surface of the earth. The need to be able to tolerate each other’s presence in a finite space creates a natural

antagonism that forces the creation of political institutions and law to contain it. In the Definite Articles of Toward Perpetual Peace Kant argues that ‘The natural state of man is not peaceful coexistence but war – not always open hostilities, but at least an unceasing threat of war’ Kant warns that ‘all men that can affect each other must stand under some civil constitution’ otherwise ‘ a man in the state of nature deprives me of this security; and if he is my vicinity he harms me – even if he doesn’t do anything to me – by the mere fact that he isn’t subject to any law…So if I can compel him either to enter with me into a state of civil law or to get right out of my neighbourhood…’2 This idea of a civil law, the Third Article, proposes that ‘the law of world citizenship is to be united to conditions of universal hospitality’. This incorporates rights that works to accommodate the antagonism of ‘unsocial sociability’; ‘The right of an alien not to be treated as an enemy’; ‘the right to visit’, and not be treated as a guest; and the right to present as a possible member of society 3.

Strangers

Kant directs individuals as members of ‘a civil constitution itself’ – the state – away from antagonism towards mutual recognition and agonistic co-operation in ‘conditions of universal hospitality’. But what of the individual or group that has no relation with a civil constitution? What of those who are ncynical of the state and self-identify as ‘citizens of the world’ 4 ? The Third Article declares ‘the right to visit, and not be treated as a guest’ but importantly this is not a right of residence. What use has the stranger of a hospitality between members of states which is based on sovereignty? Unable to

1(Kant, 1996)

2(Kant, 1996)

3(Kant, 1996)

4 A status legitimised, philosophically, by classical Greek thinking and one that historically problematizes the

relationship between the State and the citizen: First to use the word ‘cosmopolitan’, the Cynic philosopher

Diogenes identified as a ‘citizen of the world’ challenging an ipseity created through the citizenship of the

classical Greek city-state. (Laertius, 1972)

reciprocate this person is figured as the stranger, the eternal visitor, alienated and unequal. In amongst many overtly racist speculations (‘If the Turks would travel…this is done by no other people but European, which proves the provinciality in spirit of all others’) in Anthropology from a Practical Point of View 5 Kant excludes the non-European from this international citizenship when he conceives of a social hierarchy in respect to the state: The nation as united into a civil whole; a rabble, as those segregated from law; and the mob as a union of the segregated as the character of non-western races. As now permanent ‘visitors’ the contemporary experience of the sub-Mediterranean migrant in Europe is a case in point. As now ‘nomadic’ the migrant is forced to live on temporary sites and are are at odds with enclosure systems and private property. This has the effect of situating migrant culture as an implied criticism of the nation-state. This locates asylum seekers or migrants cultural status as quasi-permanent visitors in contemporary Europe, and deprives them of the possibilities of the reciprocal hospitality available to sedentary citizens of nation states. Since the Treaty of Rome in 1957 The European Community instituted the freedom of movement of persons, capital, goods and services 6 partially in response to the fragmentation of national and ethnic locations in the aftermath of the Second World War. The introduction of The Schengen Agreement of 19857 sought to create porous national borders in law, but in fact served to restrict legal free movement to national citizens of states within the European Union only, a contemporary ‘Fortress Europe’. The migrant status as strangers or as people who are culturally figured as not ‘at home’ is institutionalised in this legal framework.

Hostipitality

An impossible cosmopolitanism is aporetic like the impossibility of hospitality for Jacques Derrida: ‘Hospitality is owed to the other as stranger. But if one determines the other as stranger, one is already introducing the circles of conditionality that are family, nation, state and citizenship’8 and operating under laws that exclude the possibility of a universal hospitality. Derrida’s text reveals the ethical determination of hospitality by identifying its western heritage and etymological descent, revealing the interior contradiction of the concept, and how this is commensurate with the aporetic

5 (Kant, 2006)

6 Signed by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany the Treaty of Rome defined the

European Economic Union.

7 The Schengen Agreement started the abolition of internal border controls for citizens of member states of

the European Union.

8 (Derrida, 2000) p.8

character of western culture at large: this, in fact, is the deconstruction project. Derrida’s identity as a French Algerian Jew, and as one whose culture has suffered its’ own inhospitality and enforced nomadism within Europe and, in Derrida’s case, Algeria, enables him to construct a view from outside of the heritage he is examining (the inherited locus of power occupied by Kant and Enlightenment thought) and continually rethink the conditional as the unconditional. In the article Hostipitality written for the journal Angelaki 9 in 2000, he argues that the internal contradiction of hospitality is that in order to be hospitable a territory has to be created, and that is through exclusion, or a pre-existing hostility, like Kant’s ‘asocial sociability’. So Derrida doesn’t see

where hospitality is actually situated: how the third definitive article of Perpetual Peace, ‘cosmopolitan right shall be limited to conditions of universal hospitality’ cannot be anything other than defined by the parasitic presence of a hostility as trace or supplement presented by ‘the seed of discord’ 10 inherent to the creation of European Nation States and borders: cosmopolitics has a history and ‘therefore we do not yet know what hospitality beyond this European, universally

European, right is.’ 11 Kant’s invitation to join a league of nations for perpetual peace involves checks, customs and collision, which for Derrida become thresholds where ‘hospitality always I some way

does the opposite of what it pretends to do and immobilises itself on the threshold of itself’ 12. For Derrida Kant’s idea that the ‘right of a stranger not to be treated with hostility when he arrives in

someone else’s territory’13 misaligns the power structure of visitation ‘as a reaffirmation of mastery…hospitality limits itself at its very beginning’. 14

The roots of the aporia of hospitality is revealed in the etymology of the word: “The troubling analogy in their common origin between

hostis as host and hostis as enemy…”15 Derrida creates the neologism hostipitality that reflects the etymological contradictions: At once it’s the aporia in hospitality where it is conditional on hostility – in order to be hospitable to another one has to already have created a territory of conditionality in as much as the naming of another is a condition of subject-hood. So any invitation to the stranger is predicated on a pre-existing hostility or violence which has to be inverted:

9 (Derrida, 2000)

10 (Kant, 1996)

11 (Derrida, 2000) p.10

12 (Derrida, 2000) p.14

13 (Kant, 1996)

14 (Derrida, 2000) p.14

15 (Derrida, 2000) p.15

‘…the reversal in which the master of this house, the master of his own home, the host can only accomplish this task as host, that is hospitality, in becoming invited by the other into his own home, in being welcomed by him in receiving the hospitality he gives’ 16 And it may be this reversal of fortune, the demand that in order to be hospitable the host has to give up their mastery of their home to the visitor in order to host – the host is subject to the hospitality and generosity of the visitor to say ‘you are master of your home’ – that creates the enmity to the

stranger. The host/hostage aporia of hospitality is where ‘the one inviting becomes almost the hostage of the one invited, of the guest (hote) the hostage of the one he receives, the one who keeps him at home’ 17. The caesura created when a host cannot extend hospitality to a stranger is not just an external difference – the failure to accommodate results in the internal alienation of the subject from themselves: the host cannot know themselves without the hospitality of the stranger and so is dependent on the society of fellow humans. And this gives rise to an aporia in sociability – the tension between the supplementary antagonism of asocial sociability and the need of a visitation to know oneself, and the demand therefore for an agonistic hospitality. So if Kant can ‘compel (the stranger) either to enter with me into a state of civil law or to get right out of my neighbourhood…’ it

is only by virtue of a hostipitable ‘folding the foreign other into the internal law of the host’ 18 as an act of generosity on behalf of the visitor to creates the territory of the host.

A Place in the Northern Sun

So if ‘hospitality can only take place beyond hospitality’ where there are cosmopolitanisms that can think outside the box of European intellectual history, what form can hospitality take? In 1996

Derrida addressed the International Parliament of Writers in Strasbourg on the subject of cosmopolitan rights for migrants and asylum seekers, which in the light of France’s imposition of the law on immigrants and those without rights of residence created a new category of internal stranger in the ‘sans papiers’ or undocumented, was an occasion when Derrida forewent a theoretical deconstruction to suggest a concrete ethical intervention. Published as ‘On Cosmopolitanism’19 Derrida acknowledges the inadequacies of the contemporary State to accommodate the refugee or the immigrant as they are ‘limited by treaties between

16 (Derrida, 2000) p.9

17 (Derrida, 2000) p.10

18 (Derrida, 2000) p.14

19 (Derrida, 2001)

sovereign states’ 20 and struggle with the legal and ontological status of the person without nation or home. He doubts whether an international declaration of human rights as a third ‘host’ – working as ‘home’ for those without a civil home – could ‘transcend the present sphere of international law which still operates in terms of reciprocal agreements and treaties between sovereign states; and for the time being a sphere that is above the nations does not exist. Furthermore this dilemma would by no means be eliminated by the establishment of a world government’21 even disregarding both his suspicion of the possibilities for a despotic world-state. What Derrida wants is something more

concrete.

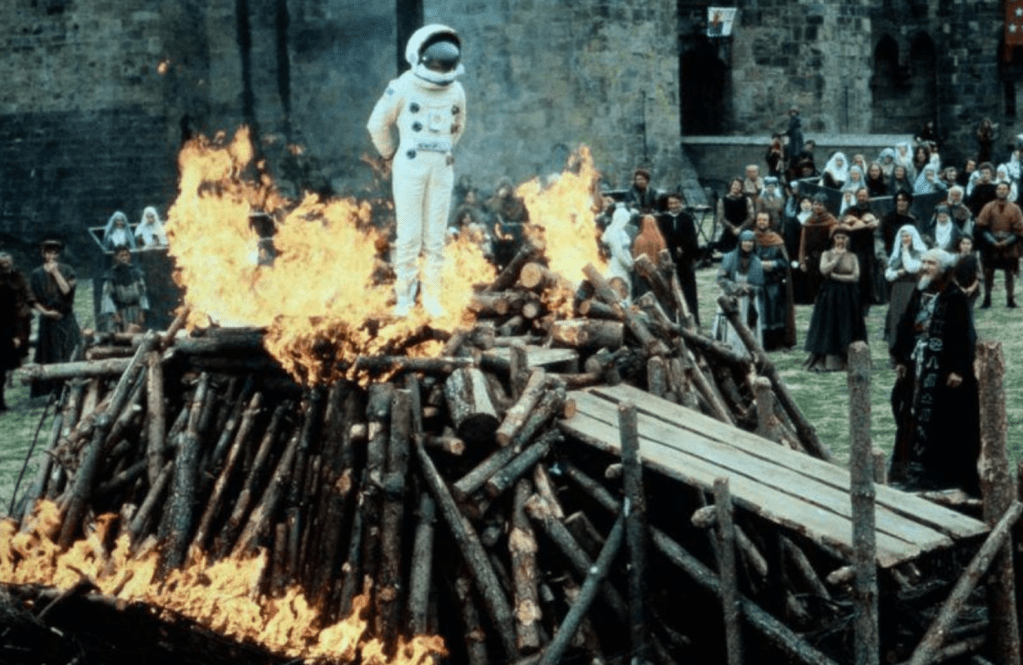

Still from ‘The Spaceman and King Arthur’ 1979 (Dir. Russ Mayberry)

In response to the International Parliament’s call for the conceptualisation of places for refuge for immigrants, Derrida identifies the city as a possible refuge in a geopolitical landscape where national

and international law has erased the originary right of residence: where ‘no one individual had more right … to live in any particular spot’ based on the ‘common possession of the surface of the earth’.22

Kant’s cosmopolitanism proposed perpetual peace by extending a universal law without limit by way of the determination of the common possession as a natural law, and therefore inalienable. Derrida

traces a tradition for a Babylonian city of refuge to the Hebraic where that God instructs Moses to

20 (Derrida, 2001) p.8

21 (Derrida, 2001) p.8

22 (Derrida, 2001) p.20

institute ‘those cities which would welcome and protect those innocents who sought refuge from what the texts of time call ‘bloody vengeance’23. The city-states of medieval Europe, enjoying semi-

autonomy from nation states, could operate ‘the Great Law of Hospitality… which ordered that the borders be open to each and every one, to every other, to all who might come, without question or

without even having to identify who they are or whence they came’.24 These medieval cities operated a kind of informal reciprocation of auctoritas or status as host that was is in constant danger of being politicised, and churches offered sanctuaries which were always in danger of becoming enclaves. The Enlightenment form of cosmopolitanism, viz. Kant’s, emerged to liberate

the city from this burden and universalise hospitality through an Augustinian Christianity where the members of the community of God (nevertheless an exclusive club, entry to be earned) were ‘no

longer foreigners nor metic in a foreign land, but fellow-citizens with God’s people, members of God’s household’. 25

However for Derrida it is the limitation on the rights of residence in Perpetual Peace as dependent upon treaties between states that makes for the debate of the rights of refuge, and conditions the aporia of Kant’s cosmopolitanism. The right for every person to have their own place in the sun is in direct conflict with ‘the common possession of the surface of the earth’. Derrida locates the solution as taking place somewhere between the two, the idea of a universal law of unconditional hospitality and the conditional laws of a right to hospitality. And the possibility that ‘The unconditional Law of hospitality would be in danger of remaining a pious and irresponsible desire, without form and without potency, and of even being perverted at

any moment’ 26 is absent in Hostipitality. Categorical difference is instrumental for Derrida: ‘…only fame will eventually answer…nobody here knows who I am… just as dog with a name has a better chance to survive than a stray dog who is just a dog in general’. 27 Thus an advantage for the migrant in the naming of a group.

Globalisation/A rustic’s ransom.

New Babylon was a disruptive and hostile proposal, set to undermine territorial integrities. Spatially it relied on concepts of ‘unitary urbanism’ developed by the Situationist Constant with Guy Debord,

23 (Derrida, 2001) p.17

24 (Derrida, 2001) p.18

25 Ephesians II. 19-20

26 (Derrida, 2001) p.23

27 (Derrida, 2001) p.15

a ‘construction of atmosphere 28’ that used air as a building material to work against the systems of exclusions and hierarchies sustained by seemingly benign conventional buildings as represented by ‘the repulsive Le Corbusier (who) was the designated enemy’:29 (Le Corbusier published the Athens Charter ‘A Place to Stay’ in 1933, a manifesto for a Fordist City, an architecture of functionality that was widely taken up in the reconstruction of post war Europe In 1958).

Squatters in Chandigarh, Punjab, North India (designed by Le Corbusier)

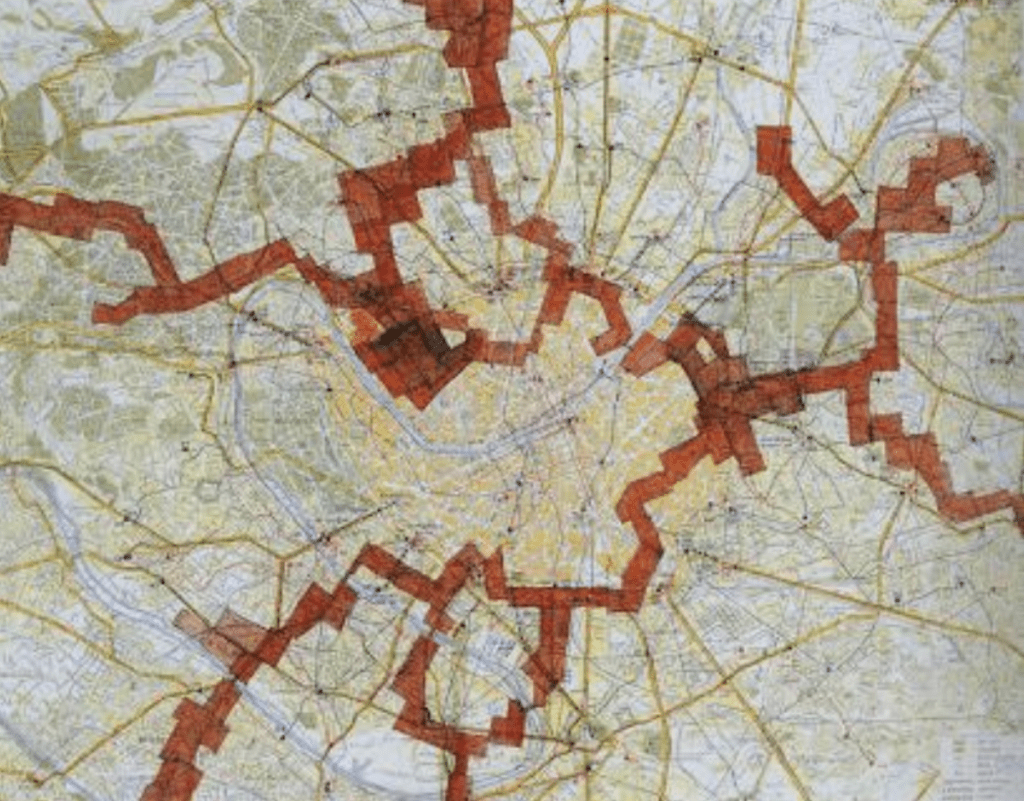

Debord was interested in the nature of the spaces in between the state or civic territories, realising space no-one possesses – the sea, deserts, wasteland, spaces of pure communication, manifesting in The Naked City (1957)31 a psychogeographic map for Paris that made connections and inscribed a territory over the top of that created by the city administration. By erasing the masters or hosts of a city in this way psychogeography makes another kind of citizenship imaginable: both as re-inscribing the general as a particular ‘City of Refuge’ within, and if conceptually extended to the global beyond nation states, as a cosmopolitan world citizenship. New Babylon’s strategy is to extend the public matter of Kant’s Republic so only the foreign remains, there is no inside from which to exclude the stranger.

28 (Hailey, 2008) p.76

29 (Hailey, 2008) p.68

30 (Corbusier, 1973)

31 Fig 3, Appendix

Intended to span the globe, Constant designed New Babylon for a ludic derive through a ‘wide world web’ 32 an architectural planetary continuity brought about by a ‘construction of atmosphere’ that anticipated the technological development of ubiquitous air conditioning: A technology that accelerated the flexibility of thermo-dynamic space to invigorate the spatial functionality of place that Debord and Constant set out to disrupt. In the essay published in October Magazine in 2002 Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas 33 reflects on a different kind of continuity brought about through the ‘construction of atmosphere’ through air conditioning: Junkspace. 34 ‘Continuity is the essence of junkspace. It exploits any invention that enables expansion, deploys the infrastructure of seamlessness. Junkspace is sealed, held together not by structure but by skin, like a bubble…Air-conditioning has launched the endless building’ 35.

If those physical and cultural spaces for cosmopolitan opportunity – of pure communication, collision-free movement or translation between nation states – as Constant’s realisation of New Babylon as ‘technical conquest’, material and virtual, have become the immutable networks of the architecture of authority themselves has the Situationist ambition of the erasure of territory become the fluid space of late capitalism, and is this the aporia in the loosening of the territorial bonds of the European project? For Koolhaas ‘conditioned space inevitably becomes conditional space’. 36 From the political left, like Braidotti, the view is of a technocratic network of air conditioned structures that has ‘dictated mutant regimes of organisation and coexistence’. Contrary to the exteriority of New Babylon 37 that feminist philosopher Chantal Mouffe envisioned as an unbound cosmo-political space enabling ‘a multitude of interactions that take place inside a space whose outlines are not clearly defined’ 38 junkspace is ‘sealed, held together not by structure but by skin, like a bubble’39 and captures the hierarchies and it’s inhabitants elaborated in Kant’s ‘Practical Anthropology’: rather than uniting a ‘civil whole’ on a planetary scale as a New Babylon, junkspace threatens to elaborate the segregations of civil states into one global junkstate – the only outcome for those unable to

reciprocate any hospitality is an interior segregation. Junkspace ‘is fanatically maintained, the night shift undoing the damage of the day shift…another population, this one heartlessly casual and

32 (Wigley, 2016) p.39

33 Koolhaas’ encounter with Constant as a journalist encourage him to become an architect, and whose influence can be seen as a key idea in OMA’s development of the ‘enclosed city’, an interior urban landscape

that minimizes private space and maximizes the public, allowing all kinds of unstructured and unregulated encounters

34 (Koolhaas, 2002)

35 (Koolhaas, 2002) p.175

36 (Koolhaas, 2002) p.176

37 Fig. 4, Appendix

38 (Tempel, 2016) p.110

39 (Koolhaas, 2002) p.176

appreciably darker, is mopping, hovering, sweeping…’ 40 and appreciably ‘another population’ of visitors who must remain hidden in another parallel strata to avoid collision. So Constant’s endeavour to create a global utopian space for nomadic races can be transfigured by the authority of the network into a global junkstate. The checks and customs of Kant’s ironic league of nations for perpetual peace prevail, and as for Derrida these become a door or threshold where ‘hospitality always in some way does the opposite of what it pretends to do and immobilises itself on the threshold of itself’. If there is a ‘hospitality (that) can only take place beyond hospitality’ through the accommodation of difference, it maybe for ‘another who is still more foreign than the one whose foreignness cannot be restricted to foreignness in relation to language, family, or citizenship’ to mediate cosmopolitanisms that can think outside the box of European intellectual history to accentuate our own particularity among the people of the world with whom we have to compromise. As Trump, Vance and Musk position immigration as the backdrop to the erosion of free speech and absurd predictions of the end of civilisation in Europe, the case maybe as well as legitimising sovereignty by ‘folding the foreign other into the internal flow of the host’ a gesture from Koolhaas’ ‘single citizen of another culture – a refugee, a mother – can destabilise an entire junkspace, hold it to a rustic’s ransom’ 41 as the trace of an impossibility that is always present within and beyond the possible. So, for Derrida, ‘the one inviting becomes the hostage of the one invited’ and therein lies the sacrifice that is the obligation of the European host.

40 (Koolhaas, 2002) p.179

41 (Koolhaas, 2002) p.180

Charlie Hardie

Leave a comment