Two exhibitions in Paris were devoted to the Belgian fashion designer Martin Margiela. One concerns his work for the eponymous label from 1989 to 2009 at the Palais de Galleria , the other at the Musee des Arts Decoratifs on his collaboration from 1997-2003 with Hermes International, creator of the most luxurious of goods. Displaying the work of a designer credited with creating stunning clothes within a radical practice that exceeded the boundaries of the fashion system the exhibitions allowed a review of his activities with two very different creatures, and asked whether it has played out as disruptive in the long term. And looking beyond the critical stylistic influence he has had on his peers and employers, asked what impact he had on the political location of contemporary designers to come such as Vetements, and their reputation as dismantlers of the fashion system?

Palais de Galleria: Hats made from recycled fur coats, and (de)constructed garments with exposed seams, linings out and tailors methodology exposed. Maison Martin Margiela AW 1997, the year Margiela moved to Hermes.

In 1981 Margiela emerged from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts alongside the Antwerp Six, a group of designers which included Walter van Beirendonck, Dirk Van Saene, Dries Van Noten, Ann Demeulemeester, Marina Yee and Dirk Bikkembergs. Immediately acknowledged for their conceptual approach, they created clothes that were both in direct dialogue with their cultural context (inheriting the confrontational aesthetic of punk, Vivienne Westwood, Jean Paul Gaultier et al.) and in a reflexive dialogue with the fashion system within which they operated. Consequently commentators have associated them with literary theories of the time, casually migrating Derrida’s Deconstruction onto their practice as well as onto all sorts of other counter-cultural activities and outputs. Margiela’s work proved particularly accommodating to this sort of theory washing. For the conceptually minded a dismantled Guernsey jumper with arms made from the lining of a tailored jacket echoed the practice of a reading and (re)writing that brought secrets to the surface, or revealed the hidden assumptions or ‘enabling conditions’ through the dismantling or close reading of cultural actors or events. Margiela’s ‘House’ had an agenda: his anonymity, refusal to do interviews, the universal studio uniform of white coats, appropriation and refiguring of vintage clothing worked to de-centre the act of creation away from a single designer-as-authority forced comparisons with the anonymity of contemporaneous art, or the loose historical appropriations of the architecture of the 1980’s. It’s true that only one or two photographs of the designer exist but rather than flattening out creative hierarchies this has produced a powerful mystique around the Margiela creative process and its ownership: good marketing, and its nigh on impossible not to credit Margiela with a knowing if not ironic familiarity with deconstruction.

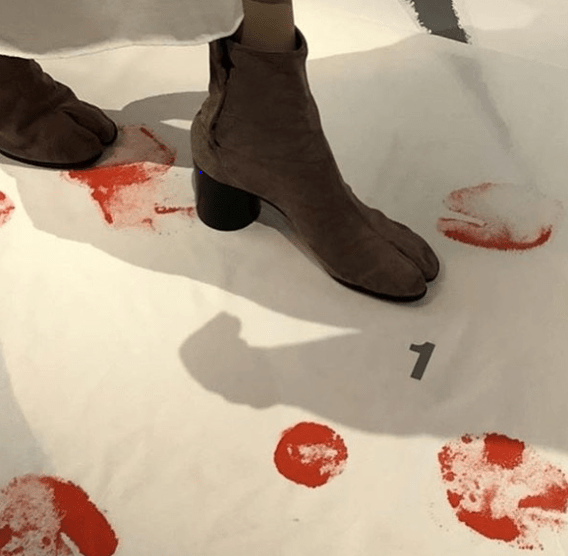

Nevertheless Margiela’s clothes do seem to speak somehow of their location. They have the tone of revelation, as if they have their own history or a story to tell about the wearer. For the ‘Doll’s Wardrobe’ collection (FW94/95) he re-presented dolls clothes that had been real clothes scaled down to dolls sizes, then brought back up to human proportions retaining the outsize zips and awkward proportions. At once figured as palimpsests, the exposed and defective tailoring brought the insides of a garment out, bearing the traces of other ways of being. And the vertiginous scales made them uncanny objects, creepy. Clothes like this that were both beautiful and analytical beg the question: what is it that these clothes speak about? Despite the conspicuously skilful tailoring and luxurious materials the inspired constructions displayed in the Galleria exhibition, like the dolls clothes, all feel shadowed or off-balance in some way. Margiela’s well known appropriation of the Japanese tabi shoe reveals what is at stake. As it migrates from an ethnic reference, a theatrical kawaii to a cloven hoof that leaves bloodied footprints across the floor of his shops, it demands acknowledgement of the entanglements in fashion of beings both human and non-human. Garments clothe and protect but fashion signifies the wearer’s cultural location. Margiela’s mode parlante talks about how clothes are totemic, become fetishised immaterial commodities invested with the intimacies and sentiments that substitute for those that are absent.

Palais de Galleria: Tabi Shoes trail hoof prints across shop floor.

If the cyclical renewal of fetish objects in the spectacle of the seasonal fashion system works to deny death and decay, Margiela conspires to reveal this. Motifs reoccur again and again, vintage designs are reworked and repeated season on season.

Margiela operates less as an auteur-designer but more as kind of keeper or curator of clothes. He presents vetements-trouves in a surrealist manner. That totems, transitional and fetish objects are traditionally animal is not lost to Margiela. His sophisticated implication of recycled luxury leather goods polished with use echoes Sigmund Freud’s ‘shine on the nose’, conjuring a glistening fetish commodity from the traces of abject body fragments. Freud’s deliciously nutty case study of fetish analyses how a bilingual young man’s desire for shiny noses ameliorates his fear of castration as he associates the German for shine, ‘glanz’, with the English ‘glans’, and an object of fear is transformed into an object of desire. A halter top made of second hand gloves jars much in the same way the surrealist artist Meret Oppenheim’s Object in Fur (1936) might:

Like Freud’s ‘glanz’, its a pun. It is both artisanal luxury and second hand leather, and like the shine on a dog’s wet nose, it is simultaneously a sign of health and repulsive. As it paws the wearers’ torso the animal skin doubles our own, forcing the wearer into an intimacy with themselves, animal others and the acts committed to produce it: Bulgarian psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva mobilised ‘abjection’ to describe this enmeshed attraction and repulsion.

Martin Margiela Glove Halter Top SS2001

Her own aesthetic pivot was the fascination with and repulsion of the skin on hot milk, a boundary between her and the animal which could ‘show me what I thrust aside in order to live… I am at the border of my condition as a living being’. This explains why stuff like horror genres, road kill, the repulsive can be so compelling. For Kristeva these breakdowns of separation, the shock of proximity to something not us were transcended in art where the abject was purified.

Margiela’s art draws the fashionable irresistibly to this kind of liminal place, the border of their condition. The proximity to wealth-signalling leather – and the more luxurious the stronger the effect – serves to confirm that the bearer will remain on the right side of death. He reveals the intimacy sought out in by actors in a fashion community: a belonging created by commitment to the shared space of collective self-destruction through boundless expenditure in pursuit of continual renewal, the irresistible charge of the communal sacrifice of commodity fetish.

Musee des Arts Decoratifs. Margiela for Hermes 1997

The strength in pairing these two exhibitions is that they support this idea: that the efficacy of commodity fetish increases with its surplus value. It might be expected that Margiela’s artisanal would louchely transform into couture in the House of one of the worlds most luxurious and conservative brands, the earthy scent that trails his oeuvre renewed as bouquet. But it testifies to the turn of the abject that, when Margiela migrated to Hermes in 1997 the stakes were actually raised. The extreme ‘care’, tailoring and luxury of Hermes’ aesthetic served to intensify rather than overwhelm the jarring tribal gaze or wig-hats made from recycled fur coats. Perhaps this argues that the abject has a foundational or structural role in the fashion system, an auto-immunity built into the practice. Or now has become an indispensable strategy for contemporary designers. Once you know it’s there, you see it everywhere: perhaps by default much has been made of Vetements’ head conceptualiser Demna Gvasalia’s acknowledged debt to Margiela and the inherited method of deconstruction (he trained in Margiela’s House), his collective approach, appropriation, recycling, ill-fitting flea market clothes etc. But maybe it is the more oblique observance of low fashion that hitch him and his collaborators to Margiela, echoing the way he was entangled with the anti-fashion of punk and ‘la mode destroy’. Vetement’s appropriation of sportswear, the manufacturers defect, the homemade and the flatness of work clothes and commercial branding: the fetish-isation of a central/eastern European stylistic ‘poverty’ that could be manifestly exploitative if it were not animated by a citizen of Georgia.

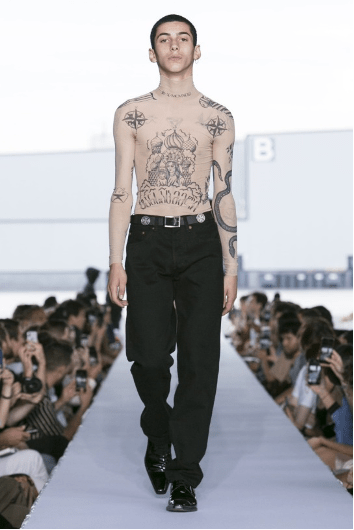

Vetements AW17/18

Perhaps what underpins Vetement’s substatial commercial and critical success is that it still disrupts despite its now well-rehearsed precedents. The ‘mundanity’ or down to earth nature of the clothes that is hiding in plain sight in the super luxurious and really expensive mash ups of cultural locations arouses the very richest consumers – one might expect the sniper shell suit seen at Paris Fashion Week on July 3rd to retail in the thousands of pounds – and testifies to how the border zone between feeling comfortable and being discomforted has such a powerful draw. Maybe as the wearers reassure themselves about upcycling and their cultural fluency is it their enmeshment with their own disgust that invites them to buy clothes that expose their own condition. Even as they separate from the herd they are forced to get their hands dirty? Kristeva’s encounter with the milk’s skin demanded that she either drink the hot milk as her parents wished, or defy them and define herself. And this is the same moment where Gvasalia can confront his creative familial hierarchy, but chooses to consume the milk’s skin instead.

Top: Russian tattoo t-shirt from Vetements SS19 show, Paris, July 3rd 2018. Bottom:A Hermes print that should be found on a silk scarf or tie becomes luxury tribal skin marking. Margiela for Hermes 1997.

Adria Ehrliche

Leave a comment